- Home

- Williams, Dee

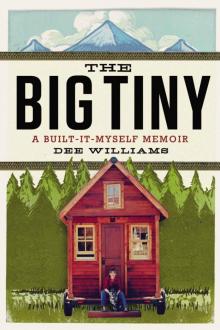

The Big Tiny: A Built-It-Myself Memoir Page 15

The Big Tiny: A Built-It-Myself Memoir Read online

Page 15

Lightning struck somewhere west of my neighborhood, and the giant flash of light gave me a chance to sit up and notice that the neighbor’s tree was bending sideways away from the wind. This was about the time that RooDee started panting and shaking, keeping her eyes on me and her ears flat to her head, whining at me like the bed was too small a lifeboat. That was also the moment that I remembered I hadn’t reconnected the grounding wire to my electrical system.

“Shit!” I yelped. “Shitty shit shit!”

The grounding cable was about as big around as my pinky finger, and normally connected the solar electric system (the battery, inverter, meter, and panels) to a copper post that was pounded four feet into the ground. This was supposed to keep the system from frying if it got hit by lightning, and now (“Oh shit!”) I realized I hadn’t reconnected the cable after moving things around the other day. I had disconnected the wire while wrestling the solar panels into a new position in the yard, a spot near the brown scab of my garden—a spot that was bleeding a few weeks ago but now looked painful to the touch. At the time, I imagined that I was smart and clever for optimizing my position under the sun, but now I was screwed; the panels were lined with metal and sat ten feet above the ground like a giant two-thousand-dollar lightning rod.

“Not so smart! Not so smart!” I whined at RooDee while staring out the window.

I had labored over whether or not I even wanted electricity in my house; it seemed unnecessary because, as I had explained to a friend, “I have a headlamp to see which part of me is standing in which part of the house.” In my estimation, there are far too many lights in the world; streetlights, car lights, tiny lights in the glove box; front and back porch lights, lights in the ceiling, under the cabinets, and in the refrigerator; lights working their way across undulating surfaces, so you could guess the couch cushions are soft and the bathroom sink will bruise your hip if you totter into it in the middle of the night.

I wondered if all that light was somehow causing us to forget things, blinding us to the truth that a little darkness can be a good thing. When I was in the hospital, lights were on all the time, day or night—lights from the heart monitor, the automatic blood pressure cuff, the nurses’ station. And then there were all the electronically induced noises: beeps and hums, and pssst-ing sounds from the oxygen generator. There were noises from my roommate; she was uncomfortable, but there was nothing I could do. I just lay there, hoping the noise would dampen, spread itself into the mattresses and the cotton blankets that they’d sometimes warm for us in a microwave oven. I wished for more silence, and then once she had passed, wanted more noise. I’m fickle like that.

But I was certain I wanted my little house to be as quiet as possible, to bypass the racket created by a humming refrigerator and a buzzing fluorescent light. I wanted a chance to hear myself breathe, and to notice that my inhalations jibe with RooDee’s and my heartbeat is making the sheet rustle. As a result, I decided to install a mere smidgen of electricity so I could cut carrots early in the morning without losing a finger and avoid putting my shirt on inside out (something I’ve done plenty of times with or without a lightbulb).

I ended up with fifty feet of copper wire stringing four wall outlets and a couple of overhead lights together, and then connected that to one of the most expensive and mystical contraptions ever: a 240-watt solar electric system. It’s a small system (“more of a suggestion than the real deal,” one guy had joked when he compared my system to the “normal one down the street”) but still an impressive-looking setup, like part of a NASA space shuttle had landed next to my house, which made me feel that something intelligent was going on in the backyard.

To this day, I have no idea how the thing works—something about how the sun frees the electrons in the silicon panels, not by warming them but by simply shining on them, which made me wonder if I should install a mirror next to the panels to generate even more electricity, or place them in water to enlarge the sunrays like how my legs look bigger when I soak them in a swimming pool. These two ideas make me wonder if I’ve just proven that I don’t know the first thing about solar electricity.

Over time, I’ve gotten comfortable with my limited understanding of what is actually happening with the system. All I needed to know was that no electricity could be generated at night, less electricity could be generated in the long dark winter, and if I tried to run an electric coffeemaker, everything would shut down (the system couldn’t supply the 1,200 watts of electricity needed to heat up the water). All of a sudden, I had to pay attention to what I was plugging in and for how long, and I also had to make sure everything with the solar electric system stayed in good condition. Nothing could ever go wrong with the magical panels, battery, inverter, or meter—nothing ever!—or I’d have to live with the consequences of getting dressed in the dark: one black sock and one white, which would seem to beam like a spotlight when I crossed my legs in a meeting.

Lightning struck again—blue-white light spun RooDee around in a tight circle, and then she began pacing from one end of the mattress to the other.

“Shit!” I shouted over the roar of wind in the eaves.

I stared at my dog for a minute, trying to decide what to do, and then suddenly shoved the blankets off and huffed down the ladder. A minute later, wearing my rain gear and a headlamp, I shimmied back up the ladder to help RooDee down to the living room, where she immediately started panting and shaking.

“Stay put,” I offered (like she had any choice), and then I stepped into the storm and closed the door behind me. The backyard was a lake, pooled up from my house to the foundation of Rita’s house. I stuck my feet in my boots and launched myself off the porch into the rain, running as fast as I could to Hugh and Annie’s garage for a wrench.

Years ago, I met a guy who had been electrocuted in his house while talking on the phone. He had been talking with his brother when lightning struck the house and traveled through the wiring, including the phone line, directly into his left ear. The jolt melted his ear and the phone receiver, and blew him backward across his kitchen. He tore the phone off the wall when he got tossed, landing on his back in his living room. The electric current entered his head and followed the lines of his vasculature, from his cranial fluid down his spinal cord, along veins, arteries, and capillaries to terminate at his left foot, where it melted the heel off his shoe. He woke up three days later in the hospital with third-degree burns and an electrical problem with his heart—a problem similar enough to mine that he also had an implanted defibrillator, which then gave us a chance to bond in the waiting room at the doctor’s office.

Somewhere in the mix of discovering we both had defibrillators, he told me about his accident and turned his head so I could see his ear was missing. “Wow, I hadn’t even noticed that,” I lied. And then he shyly let me know that my shirt was on inside out.

I was thinking about that guy as I ran from my house to the garage, wondering if all the fillings in my head, the buttons on my raincoat, or the eyelets on my boots were acting like small lightning rods. I grabbed a wrench out of the garage and headed back to the little house to reconnect the grounding wire.

When I got back, another bolt of lightning hit; this time it was closer and turned the low clouds a strange blue-white. I stretched the cable from the grounding rod near the fence back over to the house. All the while, the hood of my jacket kept getting caught up in the wind, twisting into the headlamp so I was in the dark. I kneeled next to the house and ripped the hood back, letting the rain soak my head, pelting my scalp like sand thrown through a box fan.

Ten minutes went by as I tried to unscrew the wire nut that pigtailed out of my house. It was a stubby little green wire, maybe two inches long, that terminated in a copper fitting and a nut; “stylishly hidden,” I had once boasted as I showed off the way the connection was tucked behind the wheel well and under the house.

“What a complete pain in the ass,” I shouted

in frustration.

The wrench kept getting jammed up against the trailer, and my wrists suddenly seemed to bend at all the wrong angles. Meanwhile, the rain had changed direction, causing me to shut my eyes and bow my head farther into my chest, shoving my shoulders up to my ears for protection. It was a praying posture, fitting for the situation.

My fingers were working blind: finding the nut with the left hand, twisting the wrench with the right. Scraping the knuckles on the siding, losing the nut, finding the nut . . . and so on. At one point, I heard myself making tiny mewing sounds, audible over the storm, and then there was a roaring electrical growl just before a massive kaboom!

“Ack!” I yelled.

It wasn’t lightning. The transformer posted on the telephone pole in front of Rita’s house had just exploded like a bomb blast. I spun out of my kneeling position and landed on my butt, right hand still clutching the wrench, left hand landing in the garden mud.

“Ack!” I yelled again, dazed, and then I started to laugh. I realized I hadn’t been seeing lightning at all; it had been transformers blowing up all over town, wires crackling and shorting out as they were blown by the storm into tree branches.

I noticed that my house was likely the only house lit up in the neighborhood, the only surviving source of electricity in a multiblock radius. I lay faceup in the yard, letting the rain continue to drench me. It smelled suddenly sweet, like rain and mud and no worries.

“Oh my God,” I said to my dog, snickering as I walked in the house a few minutes later. “That was epic! Ridiculous. Let me tell ya what just happened.”

I like that my day-to-day invites a bit of monkey business with nature. Sometimes it’s a big deal like a rainstorm, and other times it’s something random like the day a squirrel launched itself off the fence practically into my arms (my theory is that it thought I was a short tree). Perplexed and a little frightened, I ran across the yard and locked myself in Rita’s house; maybe I didn’t want to be a friend to the woodland creatures (my childhood dream) after all. Another time, I followed a line of ants swarming the edge of the sidewalk—an ant superhighway that went on for two blocks and ended with a cluster of ants carrying a Cheeto on their backs. It was surreal, and I took a picture of it to prove it happened.

Most of my interactions with nature are accidental collisions, like when I have to race from my house to Rita’s tap early in the morning to fill my water jug. I usually dash out wearing nothing but my underwear and a raincoat, grumbling at myself for failing to install a crazy little thing called “indoor plumbing”; I grouse and whine, and notice it really is raining hard enough to sting and that the grass has gotten so saturated it feels like a sponge cake. I might see that my new raincoat is perfect except for the fact that it doesn’t cover and the hood flops in my face, or I might notice that it’s not nearly as cold as it was yesterday, that spring has arrived, which makes me skip back to the little house.

I don’t remember noticing the subtle shift toward spring when I lived in my big house; maybe because I was so preoccupied with other things, or maybe it was simple proximity. Spring now launches itself like a space shuttle mission inches from my head, and so graphically I can practically hear the “Three-two-one, GO, GO, GO!” as the sun peeks over the garage.

Sometimes I worry that I’ll slide back into the mindless rotisserie of work and projects that guided me in my old house; I’ll fixate on one pimple in my life or get so accustomed to the way things work in the backyard—like seeing the rain grow into a lake in front of my house (as it always does in winter), that I’ll grow numb to the way nature can leave me awestruck. I worry that I’ll fall asleep at the switch, only to wake up years later and find that I can’t remember what I did last week or the month before that, nor do I recognize the old lady staring back at me in the mirror.

That said, as I’ve gotten older, I’ve found that I crave a certain predictability in each day; my alarm will ring at just the right moment, my truck will start precisely like it did the day before, and I’ll drive to the office without incident, where I’ll tap away at my computer just like always, like I’m supposed to and want to, and hope to do tomorrow. I’ll return home and walk the dog, make a bit of dinner, chat with Rita, read a book, or watch an episode of Glee. Each day will present itself and end with a string of predictable events, safe and tidy, where I can float through life as the planet rotates (again) from winter into spring, and the only rebillious thing I’ll do for months is decide not to get a flu shot.

Therein lies the challenge: The trees don’t bud out of habit, and I don’t want to sleep through my life, which is why I appreciate my less-than-convenient conveniences—a compost toilet, a water jug filled up at Rita’s spigot, and 240 watts of electricity generated out of solar panels that I don’t understand. Whatever you call them, my systems keep me plugged into the day in a unique way. They keep me sober, and that’s a good thing.

Most of the time, I appreciate the way my house is set up, but I still sometimes miss my shower. In my old house, it was my favorite place to think, and now, when I shower at work or at Rita’s, I seem more focused on getting things done as quickly as possible.

When I first arrived in the backyard, my friends would invite me over for dinner and a shower. I’d shower at Jenn and Kellie’s house, Hugh and Annie’s, Candyce and Paula’s, Justin’s, Liz’s, Jennifer’s, Mike’s, or Steve’s. Showering at work was also an easy solution; I had to go to work anyway, so why not go in early and take advantage of their hot water? The downside was that the shower looked and smelled just like the locker rooms of my youth, when I was forced to dress for gym or suit up for track practice amid twenty or thirty other girls who were just as self-conscious as me. That was thirty years ago, but the same self-conscious insecurity flared when I walked into the locker room at work for the first time. Fortunately, I’d planned right and arrived a half hour before the bike commuters arrived.

I stripped naked and placed all my clothes in an empty, open locker, wrapped myself in a towel, and donned my shower slippers. I slammed the locker closed and turned toward the showers, when I realized I’d just shut my clothes in a padlocked cabinet.

The lockers had a combination lock fixed to the front of the unit. When you signed up as a bike commuter, you were assigned a locker along with a secret combination. Apparently, the locker I’d found open was an accident, and I was left standing there in a towel, feeling my chest sink just like it did in eighth grade. I sat down on a bench and tried to think. I mulled over a couple of options, including crawling through the ventilation system to my car.

I waited in my towel for about thirty minutes, occasionally spinning random numbers into the combination lock, hoping to get lucky, until the first biker arrived. I tried not to lunge at her when she walked in, and instead smiled. “Oh, hey,” I said, “I seem to have locked my clothes in this locker.” I played it off as nonchalant, like I walked around naked in the locker room all the time. She went into the hall and called Building Services, and laughed when I thanked her and explained that I had been thinking about tossing a flip-flop out the door with a note reading: “NAKED. SEND HELP!”

After that experience, I started showering at work only if absolutely necessary and instead showered fairly regularly at Rita’s house. It was less problematic, except for the occasional need to race across the backyard wearing nothing but a towel, and it became a habit—a routine that involved me checking in with Rita even though I knew, over time, that she didn’t give a hoot. But it was our way of living together, and my way of letting her know how much I appreciated her generosity. It went like this:

Me: “Rita, can I take a shower?”

Rita: “Yes. I don’t know why you keep asking.”

Me: “I like to ask.”

Rita: “Hummm,” she’d mutter as she poked her nose back into her book.

And then when I would pop out of the bathroom fifteen minutes later, I’d

chirp: “Who’s clean?” As I walked across her living room, wearing nothing but a towel, ready to launch myself nearly naked across the backyard and into my house.

Rita: “Jesus, Mary, and Joseph! I forgot you were here.”

Me: “That was the best shower ever! In a thousand million years of people bathing and showering, that was the best!”

Rita: “Hummm,” she would say as she poked her nose back into her book.

So it started, and then continued for years.

Slack Line

There are seven Internet signals that radiate through the walls of my little house, squeezing into the living room, kitchen, and sleeping loft. I can’t access any of them because they require a password, so I trek over to Hugh and Annie’s house and ask them to plug a little forklike antenna into the Internet box that sits under their computer. Once the fork is in place and my laptop properly positioned, I can use the Internet to answer all my most important questions, like how many times does the human heart beat each day (about 100,000), is there really an island where everyone has six fingers on each hand (no), what is the average square footage of a home in America (2,349) versus the UK (815). After doing this vital research, I might watch a few videos of sleeping kittens and puppies, sitting there dumbfounded, sighing and laughing, until I remember that I came over and had Hugh plug the fork into the box because I wanted to research how to take Rita’s kitchen faucet apart and replace the gaskets to make it stop dripping. So I watch three videos of a guy taking a faucet apart, and a fourth showing the same guy explaining how to fish small screws out of the drain after you’ve accidentally dropped them while fixing the faucet.

I could spend hours doing this sort of thing, hopping from one video or fascinating bit of information to another, until suddenly I get a cramp in my calf or my eyes feel gritty, and I realize I’ve spent the past two hours hovering over my computer with my back curled like a question mark. Given that—my weak mind and my ability to follow the shiny ball of more and more and more information—it’s probably best that there’s no Internet connection in my house.

The Big Tiny: A Built-It-Myself Memoir

The Big Tiny: A Built-It-Myself Memoir